The Danish Institute for Human Rights recently published an outstanding new report on The International Promotion of Freedom of Religion or Belief: Sketching the Contours of a Common Framework. The report provides a thorough and balanced overview of the field of freedom of religion or belief (FoRB) advocacy that is helpful to all policymakers and practitioners with an interest in the issue.

Religion & Diplomacy had an opportunity ask the report’s co-authors, Marie Juul Petersen and Katherine Marshall, several questions via email about the findings and implications of the report. Juul Petersen is a Senior Researcher at the Danish Institute for Human Rights. Marshall is a senior fellow at the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University. Both are members of the TPNRD Academic Advisory Council. What follows is a transcript of our conversation.

Religion & Diplomacy: A key message of the report is that FoRB promotion must be embedded within a larger human rights framework, and yet the report also notes that the language of “human rights” can be alien and even threatening and thus counterproductive in some contexts. How can we balance that tension?

Religion & Diplomacy: A key message of the report is that FoRB promotion must be embedded within a larger human rights framework, and yet the report also notes that the language of “human rights” can be alien and even threatening and thus counterproductive in some contexts. How can we balance that tension?

Petersen and Marshall: There are real tensions around different understandings of FoRB, but the priority objective is to bring these differing understandings back into coherence and alignment. That means a willingness to address areas of tension (for example around speech and women’s rights) and to build on the core, shared values and objectives of human rights.

One of our key recommendations is to ensure that interventions have strong local anchorage. Efforts to strengthen the local legitimacy and resonance of FoRB are an important part of this goal. The language of human rights, and FoRB in particular, rings hollow and alien in many contexts, and must be adapted and adjusted to local contexts, incorporating local values, knowledge, and practices through processes of translation, vernacularisation, and localisation. This conclusion resonates broadly with insights and experiences from many of the practitioners we talked to, who emphasisedthat terms like co-existence, tolerance, dignity, and intercommunal harmony can be more useful than explicit FoRB language. A FoRB activist in an Asian country noted that “the classical wordings, say in the UN Declaration on Human Rights […], have come to be stigmatized and regarded by some as negative. This does not mean that we consider the Declaration as wrong, but it does mean that we need to steer clear of negative perceptions and understandings [and use] a more acceptable and creative language while affirming the principles behind FoRB and its purposes.”

To this end, religious narratives can be important tools. Reliance on religious narratives can be—and is often—useful in translating the human rights language into something that has broader resonance and legitimacy in local communities. Experiences of FBOs and religious leaders involved in interfaith initiatives, capacity-building, and training show that an emphasis on the religious origins of human rights and identification of common values can go a long way in demystifying FoRB, providing justifications for interreligious collaboration and tolerance among participants.

But there are also risks and dilemmas involved in such processes of vernacularisation. While there are obvious overlaps between FoRB and consensus-oriented notions of co-existence, harmony, and tolerance, they are not the same, and there is a risk that important elements of FoRB are ‘lost in translation’ so to speak. FoRB is a right of the individual to practice or not practice his or her religion or belief, even when this leads to disagreement and lack of societal cohesion. An emphasis on co-existence and harmony can downplay or overlook issues that contribute to such disagreement and conflict, including issues around gender equality and criticism of religion, which may be used as justifications for restricting the space for certain aspects of FoRB. Here, notions of citizenship, equality and non-discrimination may present more promising avenues than an explicit focus on FoRB or human rights per se.

R&D: You argue that the attempt to draw attention to FoRB by calling it the “first freedom” is not helpful. Why is that?

Marie Juul Petersen.

Photo credit: Danish Institute for Human Rights

Petersen and Marshall: Among some FoRB promoters, there is a tendency to emphasise an understanding of FoRB as the most important of all human rights. This is understandable, insofar as FoRB was for many years an overlooked right, in dire need of attention. Few mainstream human rights actors paid much attention to FoRB. Dominated by an understanding of religion as something whose importance would fade with modernisation, or at least recede to the private sphere, most human rights actors paid little attention to religion, seeing religion as at best essentially irrelevant to human rights, at worst a source of violations of human rights. From this perspective, FoRB came to be seen as ‘a luxury’ or ‘a lesser right’ as some FoRB activists put it in our interviews. This is obviously deeply problematic from a human rights perspective.

Nonetheless, an understanding of FoRB as ‘the first and foremost right’ is arguably just as problematic. An overemphasis on the prominence of FoRB can lead to skewed interventions, overlooking other aspects and rights involved in religiously related discrimination and persecution. A FoRB perspective is not necessarily the sole or most relevant perspective through which to understand and tackle such conflicts. Furthermore, and equally problematic, an understanding of FoRB as the most important right sometimes entails assumptions that this right is potentially at odds with, and trumps, other rights. Perceptions of a clash between FoRB and rights related to gender equality, sexual orientation, and gender identity are common examples. Further, putting the stress on FoRB over other elements of human rights can obscure the complex intersections among different aspects of rights, for example related to speech and assembly.

In the report, we argue for the need to ‘right-size’ the role of FoRB in the broader human rights framework, to paraphrase Peter Mandaville. FoRB is not less important than other rights, but neither is it more important. The indivisibility of human rights, and the interconnectedness between FoRB and other rights are essential.

R&D: The report notes the “almost explosive interest in [FoRB] and an emerging consensus on the importance of strengthening the international promotion of FoRB.” And yet the report also highlights the worrying downward global trend in respect for FoRB. How are these two trends related? Are FoRB-respected governments and NGOs simply responding to the threats to FoRB and they simply haven’t been effective in reversing the macro-level downward trend for FoRB? Is it possible that FoRB advocacy somehow might be contributing to the problem is seeks to solve?

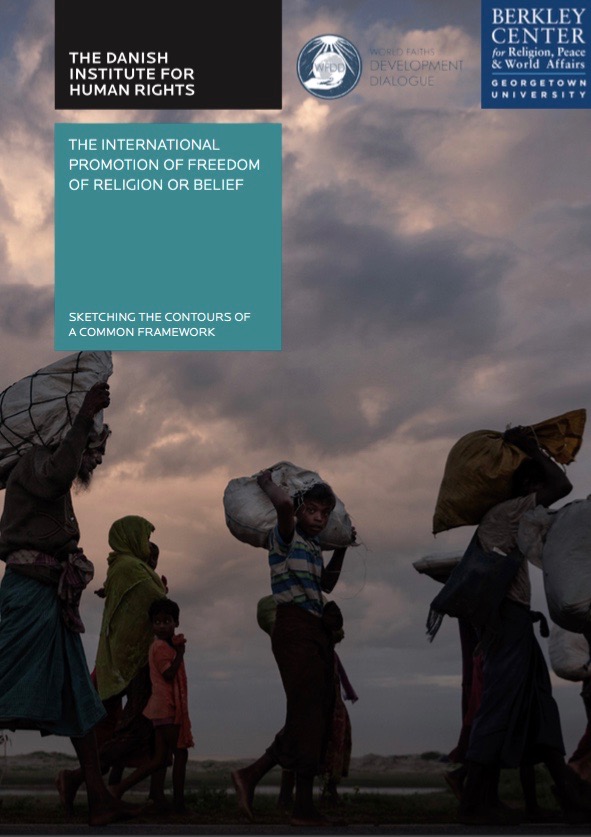

Petersen and Marshall: There is a very straight-forward relationship between the two insofar as the increased attention is, at least in part, a response to the global increase in human rights violations on the grounds of religion or belief.The situation of Christians in the Middle East has attracted particular attention in Europe and North America, sometimes connected to domestic politics around immigration and integration. The persecution of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar has also contributed to placing FoRB more firmly on the agenda, including among actors outside Europe and North America, with the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation as an active—although far from unproblematic—player.

Katherine Marshall. photo credit: Berkley Center

But there is also a more troubling relation between the two. While we think it is stretching it too far to say that FoRB advocacy is contributing to FoRB violations, there is definitely some truth to saying that certain (mis)understandings of FoRB might contribute to increasing polarisation and particularism, by extension threatening key human rights principles of universality and pluralism. There is, among some religious freedom advocates, a tendency to equate FoRB with protection of religious minorities, and more problematically, with protection of particular religious minorities. Among conservative Christian organisations in the US, for instance, many contend that the most pressing FoRB concern is persecution of Christians in the Middle East. Conversely, certain Muslim actors argue that discrimination against Muslim minorities in Europe and North America is what should be the primary cause of concern for the FoRB community. Prioritising notions of intra-religious solidarity over ideas of a common humanity, such approaches can lead to particularism and polarisation. A long-time observer and activist in the field notes: “This is a kind of ‘we have some of your people, you have some of our people’ approach.” Furthermore, it is questionable whether such an approach is pragmatically wise, insofar as it arguably leads to accusations of sectarianism at local levels, potentially damaging the work of religious minorities and FoRB advocates.

A further dimension worth focus is the absence of clear and shared approaches, among advocates and responsible government officials, to addressing the deteriorating picture on FoRB. There is an urgent need for dialogue and better understanding and a willingness to address what amount to severe challenges to human rights and to concepts of pluralism and citizenship.

R&D: Why is it that the global trends for FoRB are currently negative (e.g. more intolerance and persecution) while so many other long-term trends (e.g. less war, less crime) are positive?

Petersen and Marshall: The current global trends that favor populism, nationalist and religious identity politics, extremism, and authoritarian patterns of governance are deeply troubling and are related to intolerance and persecution. Some responsible factors seem clear: certain leadership styles and both the practical consequences of large refugee flows and the way they have been presented to host communities are examples. Insecurity as perceived even by wealthy communities is a factor. This points to the need for a strong grip on facts and a willingness to address fears and address grievances such as corrupt practices and crime. Among others who can lead in these directions are religious leaders, working closely with non-religious leaders to emphasize the core values that allow for respect and tolerance.

R&D: Those looking for a singular, overarching explanation for FoRB violations or solution to FoRB violations are going to be disappointed. Why?

Petersen and Marshall: A key point in our report is that context matters, and perhaps with particular force in the field of FoRB promotion. Further, FoRB violations are rarely a simple and direct matter of religious belief (or non-belief): many other factors are involved, including political and economic factors, ethnicity, historical memories, and so forth. Given the deep complexities and highly context-specific challenges that characterise this field, diversity and pluralism in responses is obviously key. As such, the report makes no pretence of presenting a one-size-fits-all strategy or a generic theory of change for international FoRB promotion.Instead, it aims more modestly to sketch the contours of a common framework for understanding and approaching international FoRB promotion and, through this, to provide inspiration and basic guidance to support actors in their development of context-specific theories of change and strategies.

R&D: You note that the original aim of the report was to “collect examples of successful (as well as less successful) initiatives in the area of international FoRB promotion, and, based on an analysis of these, to draw out a general theory of change, contributing to a more evidence-based approach to the international promotion of FoRB.” Due the scale and complexity of such an undertaking, the report offers a more modest survey of the field of FoRB promotion. What would it take to actually complete a research project as originally envisioned?

Petersen and Marshall: While we doubt that it is possible—or in fact desirable—to draw out a general theory of change in this area, it would certainly be useful to engage in a more systematic, large-scale collection of evidence than we were able to do, given the time constraints of the project. If the international FoRB promotion is to be strengthened, we need much more solid knowledge about what works and what doesn’t work. However, one significant problem here is the paucity of information on the effects, impact, and consequences of international FoRB promotion. While initiatives encouraging the sharing and exchange of knowledge, experience, and evidence among actors in the field are on the rise, few robust efforts have set out to document this experience systematically. There are few systematic, longitudinal research studies of the various approaches to and interventions in the field of international FoRB promotion. At the level of project and programme evaluations and assessments, solid examples are also few and far between. Various factors explain these gaps. They include the newness of the field, sensitivities surrounding many initiatives, and, not least, the notorious difficulties in measuring and evaluating the kinds of goals that FoRB promotion seeks to achieve – whether change of societal cultures, changes in government behaviour, or strengthened international norms around FoRB.

R&D: The report contends that FoRB entails both individual and collective dimensions. How can we promote collective FoRB rights without giving ammunition to those who want to claim that “religions” have rights (e.g. the supposed right of Islam to not be defamed)?

Petersen and Marshall: The collective dimension of FoRB is essential. It is impossible to imagine full enjoyment of FoRB without the right to e.g. practice your religion or belief in community with others, to celebrate religious holidays and feasts together, or to establish and maintain common institutions of worship. To promote and protect the right of religious and belief communities to engage in such activities, however, is very different from arguing that religions have rights, as reflected e.g. in the defamation of religion agenda or in the many blasphemy laws around the world. In fact, such protection of religion tends strongly to lead to and justify violations of many individuals’ and communities’ right to FoRB. The protection of one person’s or group’s religion against criticism, defamation or insult will most often result in restrictions on another person or group’s right to express and practice their religion or belief.

As important as collective rights are, it is important to emphasise that FoRB is first and foremost a right of the individual to practice or not practice his or her religion or belief, even when this goes against the values and doctrines of the religious community of which he or she is a part. Religious communities sometimes engage in discriminatory and oppressive practices against individuals; even persecuted religious minorities may be highly patriarchal with values, practices and traditions that undermine the rights of e.g. women and LGBTI people. An approach that equates FoRB promotion with protection of collective rights risks overlooking or sidelining such important aspects. FoRB aims to ensure the right of individual women and LGBTI people to interpret and practice their religion as they want, even when this runs counter to the orthodoxy of the religious group or community of which they are a part. Muslim women’s rights organisations such as Musawah and Alliance of Inclusive Muslims, for instance, work consistently to empower women to claim their right to speak for themselves and interpret their religion in a way that is consistent with principles of equality and non-discrimination.

R&D: There are some voices in the West who contend that the full right to FoRB cannot be extended to Muslims because Islam is inherently monopolistic, discriminatory, and even violent. And they point to the situations in Muslim-majority countries to substantiate their claims. How does your report challenge that line or argument?

Petersen and Marshall: Yes, in current debates on FoRB it is sometimes argued that somereligions, due to their particular theological doctrines, are inherently more prone to intolerance and violence than others (or to disrespect for certain human rights), thus explaining higher incidence of human rights violations in general, and FoRB violations in particular. This argument is typically extended as an explanation for the seemingly high level of FoRB violations in Muslim-majority countries compared to other countries. Jonathan Fox has explored this question in depth and his research confirms that in general, levels of discrimination against religious minorities are far higher in Muslim majority countries than in Christian majority countries (Fox 2016:161). However, he finds that religion (or, more specifically, Islam) alone cannot explain these differences, given wide differences among Muslim majority states. Muslim majority states include both some of the world’s most and least discriminatory states, with high levels of discrimination in the Persian Gulf, mid-levels in other Middle Eastern states; and levels in Sub-Saharan African states similar to those of Western democracies (Fox 2016:196).

However, that particular religions are in themselves a poor predictor of FoRB violations does not mean that particular religious interpretations do not play a role in creating conditions that are conducive to FoRB violations. Most of the world’s religions are open to a multitude of different interpretations. While religious beliefs can obviously be as a strong source for reconciliation, encouraging peaceful co-existence, forgiveness, and tolerance, as documented e.g. in the involvement of religious actors in peace-building and conflict resolution throughout history, religious doctrines, traditions and norms also present powerful narratives and framings that encourage and justify discrimination and exclusion. In many Muslim majority contexts, both state and societal interpretations of Islam have in recent decades been dominated by strongly dogmatic currents, with Islam being used to justify severe restrictions on FoRB. But we also see tendencies towards more restrictive, exclusionary interpretations in many other religious contexts, whether among Hindu nationalists in India, Orthodox Christians in Russia, or Buddhists in Myanmar and Sri Lanka.

R&D: There always seems to be a debate over whether a FoRB violation or situation of religious intolerance or conflict is fundamentally about religion or really a manifestation of some deeper, underlying, non-religious issue. How does your report help us think about that debate?

Petersen and Marshall: One FoRB expert we talked to noted that: “We all like simple solutions. When we talk about FoRB, we think that it can only be about religion, that there cannot be other reasons. But discrimination and persecution is also about economy, social factors, politics, culture, history. The world is complex.” And he is very right. No single factor or even combinations of factors can consistently explain why and when some countries and communities violate FoRB and to what degree. FoRB violations—like broader human rights violations—rarely have a simple, straightforward cause, but are shaped by complex webs of interrelated and intertwined factors, distinct in each particular context. In-depth context analysis is needed to begin to understand these complexities. In our report, we point to a number of factors that may be relevant to creating conditions for FoRB violations and as such, are useful to explore and analyse in particular contexts. The factors we find to be of particular relevance in analysing and explaining violations are—not surprisingly—conflict and violence; poverty and inequality; authoritarian or weak state structures; official state religion, and broader cultures of intolerance, including also particular religious interpretations and traditions.

Apart from contributing to context analysis and understanding of FoRB violations, our analysis points to insights that are relevant to the design of strategies for FoRB promotion. If FoRB violations are most likely to occur in contexts of conflict, poverty, authoritarianism, and state religion, initiatives to promote FoRB should ideally be conceived as part of, and integrated into, broad-based strategies for peace-building, economic development, humanitarian aid, democratization and good governance, aimed at tackling the root causes of violations. FoRB is often, explicitly or implicitly, an integral part of the numerous policies and strategies that focus on efforts for prevention of violent extremism and counter-terrorism, but there is far less focus on FoRB issues in the areas of peace-building, economic development, humanitarian aid, democratization and good governance, despite obvious overlaps and synergies.

R&D: You commend inter-religious dialogue in pursuit of FoRB but also offer some cautions. Why is that?

Petersen and Marshall: Interreligious dialogue often—although not always—seems to be based on underlying ideals of harmony, co-existence and shared goals as the end goal of dialogue. And that is certainly a worthwhile goal. But there is merit in considering the potential pitfalls. Is there, for instance, a risk that such goals may inadvertently discourage or even decrease the space for the criticism and discussion that is so central to FoRB? Could there be ways to encourage not only agreement, but discussions and profound disagreement? The ability to make room for such disagreements—without turning to violence—is precisely what characterises a truly democratic society with respect for human rights. FoRB is, as the former UN Special Rapporteur, Heiner Bielefeldt, has noted ‘a non-harmonious peace project’.

Furthermore, interreligious dialogue is often implicitly based on an understanding of religion as a collective identity. Interreligious dialogue is predicated on the understanding that religious communities are relatively distinct, well-defined entities, and that divides between different religious communities are important. Whether they are formal religious authorities or laypeople, people participate in the dialogue because they belong to a religious community, and they are assumed to somehow represent this community. As such, there is a risk that interreligious dialogue initiatives overlook the diversity and even discords that exist in every religious community, prioritising those voices that belong to the majority, and overlooking marginalised, periphery voices, or voices that go against the orthodoxy of the religious community.

Finally, interreligious dialogue is – almost by definition – about religion. And religion is important to people. But it is not the only value system of importance. In almost all societies around the world, we find atheists, humanists, and other people with non-religious beliefs who are equally driven by particular sets of values, ideas and traditions. As a method or tool to promote FoRB, then, interreligious dialogue approaches need to include greater attention to the importance of non-religious world views and values, and an openness towards the inclusion of non-believers as important actors in any value-based dialogue.

R&D: The report stresses the need to be committed to FoRB engagement over the long haul, and you quote one practitioner who said “We are finding that for real change to happen, you need ten years.” What advice, then, would you have for politicians, diplomats, and officials who want to promote FoRB but operate with time scales much shorter than a decade?

Petersen and Marshall: Be patient! But impatient at the same time. Change takes time and persistence and efforts to promote FoRB commonly involve long term, often slow gestating work and relationships. Regardless of what strategy you pursue, there are no quick fixes. Political pressure is most successful if sustained over extended periods of time; relational diplomacy and constructive engagement need time to cultivate the trust and confidence necessary for changes to happen; educational initiatives are worth little without long-term commitments to change curricula and train teachers; capacity-building workshops must be followed up by resources and support to ensure the application of the acquired tools, and so on. In an environment where much action is driven by immediate concerns arising from the news cycle, political turbulence, and short budget horizons, this long-term focus is difficult to achieve. But it is worth underscoring its importance again and again.

R&D: What surprised you—or alarmed or interested you—the most in course of conducting the research for this report?

Petersen and Marshall: One alarming – although perhaps not surprising – finding was the many misunderstandings and misuses of FoRB that seem to flourish among a wide variety of actors. Particularly troubling is the understanding of FoRB as a right that protects religious groups and individuals rather than more broadly as a right that protects both religious and non-religious groups and individuals. When a recent UN Special Rapporteur report emphasised freedom from religion, the Vatican, among others, reacted strongly, disputing that freedom from religion is covered by international human rights law, and noting that the “use of the term freedom from religion […] reveals a patronising idea of religion, going beyond the mandate of the special rapporteur.”[i] While not necessarily using such strong language, or sharing the principled opposition, some FoRB activists are concerned that broadening the coverage of FoRB may result in a thinning of protections for all. Furthermore, in practice, many FoRB activists and organisations do seem to focus primarily on religious minorities in their work, more than on the overall societal conditions that can assure genuine respect for freedom to practice one’s beliefs (religious and otherwise).

Underlying this emphasis on religious groups and individuals is sometimes a very particular understanding of what kinds of religion constitute ‘authentic’ or ‘true’ religion, typically prioritizing more conservative orthodoxy over alternative interpretations that challenge such orthodoxies. Conservative Evangelical NGOs, for instance, tend to oppose LGBTI-friendly interpretations of Christianity. Few state this as explicitly as Tony Perkins, president of the US Family Research Council, who, when asked about Christian homosexuals arguing for same-sex marriage from a FoRB perspective noted that: “true religious freedom” applies only to “orthodox religious viewpoints.”[ii] Similarly, it is difficult to imagine the OIC standing up for Muslim women’s rights activists who are being harassed by religious leaders for insisting on a feminist reading of the Qur’an. Among secular human rights organisations, conversely, this misperception of FoRB as a right that primarily concerns conservative religious communities and individuals is, in part, to blame for their lack of engagement with FoRB.

R&D: Are you ultimately optimistic about the prospects for FoRB?

Petersen and Marshall: No. But also yes. There are examples of societies that have emerged from bitter conflicts centered on religious institutions and beliefs that show that tolerance and compassion are possible! A key factor is to advance the critically related challenges of resolving today’s conflicts, making progress on education and health, and resolving the critical issues for refugees.