In times of crisis, humans have a tendency to turn to religion for comfort and explanation. The COVID-19 pandemic is no exception. This crisis has increased Google searches for prayer (relative to all Google searches) to the highest level ever recorded. In this article I will explore what we can learn from daily data on Google searches for 95 countries and I will suggest several ways this recent spike in religiosity may impact international political and economic life. The results are based on my recent research (Bentzen, 2020).

The Rise in Prayer Intensity

Google searches for religious terms, as a share of all Google searches, provides a signal of peoples’ interest in religion in real time. Research has demonstrated that our behavior on the internet reflects our personal interests and the actions we take in the real world (Moat et al., 2016; Olivola et al., 2019; Ginsberg et al., 2009). Likewise, whether or not we search for religious terms on the internet reflects our religious preferences (Yeung, 2019; Stephens-Davidowich, 2015).

My main analysis (Bentzen 2020) focuses on searches for the topic of prayer, including all topics related to prayer in all languages. Searches have risen for other religious terms such as God, Allah, Muhammad, Quran, Bible, and Jesus, and to a lesser extent searches for Buddha and the Hindu gods Vishnu and Shiva.

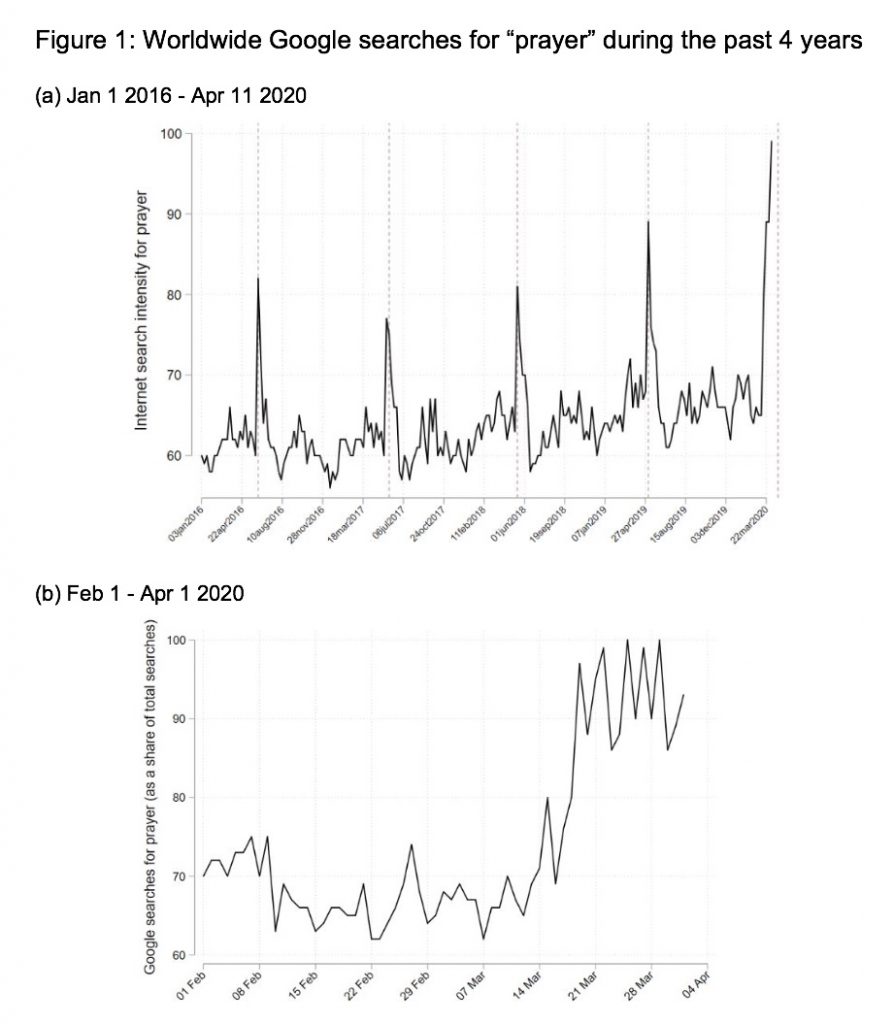

Events that instigate intensified prayer are clearly visible in the data. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Ramadan contributed to the largest yearly increase in the global search intensity for prayer (see panel A of Fig. 1). Also, prayer search shares spike globally on Sundays. Searches for prayer surged in Iran on January 7, 2020, coinciding with the funeral of Qassem Soleimani, the Iranian major general killed by US troops; in Australia on January 5, 2020, when the movement “Prayer for Australia” swept across the world in the midst of the unprecedented bushfires; and in Albania on November 26, 2019 when a 6.4 magnitude earthquake struck the country.

In March 2020, the share of Google searches for prayer surged to the highest level ever recorded, surpassing all other major events that otherwise call for prayer, such as Christmas, Easter, and Ramadan (Fig. 1). The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020. The level of prayer search shares in March 2020 was more than 50% higher than the average during February 2020. The surge in Google searches for prayer was 1.3 times larger than the rise in searches for takeaway (or “take-out” in American English).

Google searches for prayer relative to the total number of Google searches. The maximum shares were set to 100. The searches encompass all topics related to prayer, including alternative spellings and languages. The vertical stippled lines in panel (a) represent the first week of the Ramadan. The period in panel (a) is the longest period for which comparable data was available at the time of writing. The period in panel (b) is the period used in the main analysis (starting before COVID-19 became a pandemic and ending before the onset of Easter and the Ramadan). Source: Bentzen (2020).

When googling prayer, one finds many texts to use for praying. Prayers that traditionally may have been recited from memory or read from a book are now found on the internet. One of the most common prayer-related searches in March 2020 was “Coronavirus prayer”. One can find an array of prayers that ask God for protection against the coronavirus, to stay strong, and to thank nurses for their efforts. According to a recent Pew Research Center survey, more than half of Americans have prayed to end the coronavirus (Pew, 2020b).

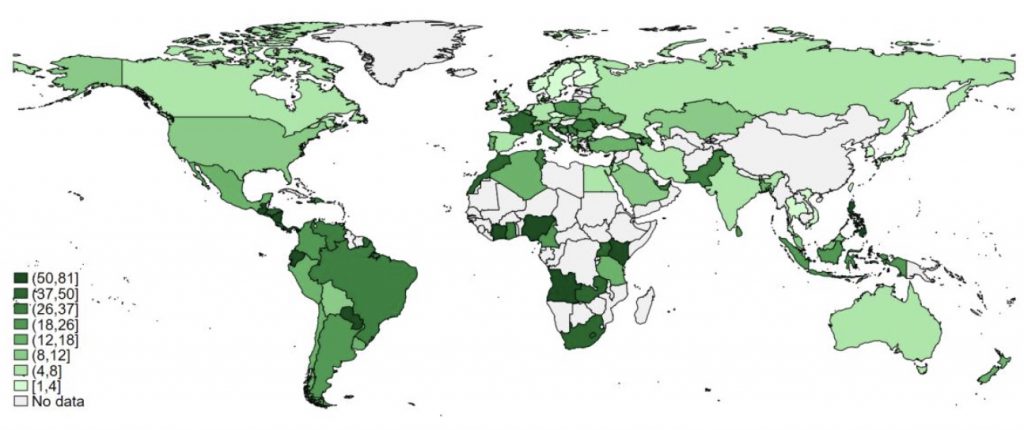

Using daily data on Google searches for prayer from 95 countries across the globe, I find that the rise visible in Figure 1 occurs around March 11 for most countries, and increasingly so after their own populations had been infected. The rise in prayer has been a global phenomenon. All countries, except the 10% least religious, saw significant rises in prayer search shares. Figure 2 illustrates which countries saw the largest rise in searches for prayer, indicated by darker shades of green. The largest increases occur in South America, Africa, and Maritime South East Asia, some of the most religious regions of the world. In general, the rise in searches for prayer was higher for the more religious societies. Prayer searches rose for all major religious denominations, especially for Christians and Muslims. The rise was more modest for Hindus and Buddhists.

Figure 2: The rise in prayer search shares across the globe in March 2020

Darker green indicates larger rises in prayer search shares. Missing data is indicated with grey. Source: Bentzen (2020).

Prayer search shares rose more in poorer, more insecure, and more unequal countries, which may indicate that people pray more in areas with larger needs for comfort and soothing. But this impact is exclusively due to these countries being more religious. This indicates that people logically use religion more for coping in areas where religion already plays an important role.

To get a sense of the share of the global population that prayed as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, I combine the results described above with the Pew (2020b) survey documenting that more than half of Americans had prayed to end the coronavirus. Since the US has a level of religiosity equal to the median level of religiosity in the world and since religiosity is the main factor that determines whether countries use religion for coping, it seems safe to conclude that more than half of the global population had prayed to end the coronavirus by the end of March 2020.

Religious Coping

The main reason for the rising interest in prayer on the internet is religious coping. People use their religion to cope with adversity.2 They pray for relief, understanding, comfort, courage, and perseverance. Research has documented that struggles with cancer, a death in the family, or severe illness are correlated with a heightening of religiosity. Recent research also shows that adversity in the form of natural disasters causes people to use their religion more intensively (Bentzen, 2019; Sibley and Bulbulia, 2012).

People may google “prayer” for a reason unrelated to religious coping. They may be searching for online forums to replace their physical church gathering that were suspended during the pandemic. Theoretically, we would not expect this to be the main explanation for the rising search shares for prayer. To cope with adversity, people tend to rely mainly on their intrinsic religiosity (such as private prayer) rather than their extrinsic religiosity (such as churchgoing).3 In addition, a recent survey reveals that 94% of Americans who pray, pray alone, while only 2% pray collectively in a church (Barna, 2017).

Another survey shows that 24% of Americans report that their faith has strengthened since the onset of the corona crisis, which we would not have predicted if people are simply replacing their physical churchgoing with online church (Pew, 2020a). They must be doing something that strengthens their faith. The empirical results support that replacement of physical churches is not the main reason for the rise in Google searches for prayer. For instance, searches for the topic “internet church” also rise, but follow a distinctly different pattern than the prayer searches and is of a much smaller magnitude. Also, the search shares for prayer continue to rise long after the church closures. Further, the rise in prayer searches is not limited to Sundays, when most services are held, but occur on all days of the week, except Fridays. These results are consistent with people praying to cope with their fear of the coronavirus.

There are reasons to believe that the true rise in prayer is potentially much larger than what is visible from Fig. 1. First, most prayers are performed without the use of the internet, instead recited from memory, read from physical books, or simply offered extemporaneously.

Second, among those who use the internet to find prayers, the data encompasses only those who google “prayer,” while those who enter the prayer-related websites directly are not included.

Third, the elderly, who were most severely affected by the pandemic, are not the most active internet users and thus their prayer intensity will not be fully captured by the Google data.

Fourth, the month of March 2020 saw an even larger rise in internet searches related to COVID-19 and other topics since people across the globe were at home due to lockdowns. This mechanically reduces the search shares for other searches, including prayer.

Fifth, the data includes only countries with enough internet users (as defined by Google Trends) and thus the poorest countries or countries with restricted internet access, such as China, are not included. People in poorer countries are on average more religious and thus more prone to engage in religious coping.

At this point in time, we can only speculate whether religiosity and the role of religion will rise more permanently, but previous research has found that natural disasters leave a long-lasting impact on religiosity (Bentzen, 2019).

Potential Economic Impact

The COVID-related rise in religiosity may impact the economy in various ways. First, a large part of the economic downturn in the face of COVID-19 is due to economic anxiety (Andersen et al., 2020; Fetzer et al., 2020). If religion lessens anxiety, religious societies may experience lower reductions in consumption.

Second, COVID-19 may increase religiosity permanently, in turn impacting the economy. I have found in my previous research that earthquakes increase religiosity permanently across generations (Bentzen, 2019). Other scholars have documented correlations between religiosity and socio-economic factors such as people’s ability to cope with stress and uncertainty, criminal behavior (Guiso et al., 2003; Miller et al., 2014), GDP growth, and traditional gender roles (McCleary and Barro, 2006; Inglehart and Norris, 2003).

Third, rising prayer intensity reveals that people from across the globe experience emotional distress in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, and they use religion to cope. The economic consequences of these emotional effects may be large, as illustrated by a study by Andersen et al. (2020), documenting that the economic downturn is mainly caused by the perceived risk of the virus rather than by government mandated lockdowns.

Jeanet Bentzen is Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Copenhagen.

References

Andersen, Asger Lau, Emil Toft Hansen, Niels Johannesen, and Adam Sheridan, “Pandemic, Shutdown and Consumer Spending: Lessons from Scandinavian Policy Responses to COVID-19,” arXiv pre-print, arXiv:2005:04630, 2020.

Ano, Gene G and Erin B Vasconcelles, “Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis,” Journal of clinical psychology, 2005, 61 (4), 461-480.

Baldwin, Richard and Beatrice Weder di Mauro, “Economics in the Time of COVID-19,” VoxEU Book, 6 March 2020.

Barna Research, “Silent and Solo: How Americans Pray,” Barna Group, 2017, June 5.

Bentzen, Jeanet Sinding, “In Crisis we Pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 Pandemic,” CEPR Covid Economics 20, 2020.

Bentzen, Jeanet Sinding, “Acts of God? Religiosity and Natural Disasters Across Subnational World Districts,” The Economic Journal, 2019, 129 (622), 2295-2321.

Fetzer, Thiemo, Lukas Hensel, Johannes Hermle, and Chris Roth, “Coronavirus perceptions and economic anxiety,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.03848, 2020.

Ginsberg, Jeremy, Matthew H Mohebbi, Rajan S Patel, Lynnette Brammer, Mark S Smolinski, and Larry Brilliant, “Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data,” Nature, 2009, 457 (7232), 1012-1014.

Guiso, L., P. Sapienza, and L. Zingales, “People’s opium? Religion and economic attitudes,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 2003, 50 (1), 225-282.

Inglehart, R. and P. Norris, “Rising tide: Gender equality and cultural change around the world,” Cambridge University Press, 2003.

McCleary, R.M. and R.J. Barro, “Religion and economy,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2006, 20 (2), 49-72.

Miller, Lisa, Ravi Bansal, Priya Wickramaratne, Xuejun Hao, Craig E Tenke, Myrna M Weissman, and Bradley S Peterson, “Neuroanatomical correlates of religiosity and spirituality: A study in adults at high and low familial risk for depression,” JAMA psychiatry, 2014, 71 (2), 128-135.

Moat, Helen Susannah, Christopher Y Olivola, Nick Chater, and Tobias Preis, “Searching Choices: Quantifying Decision-Making Processes Using Search Engine Data,” Topics in cognitive science, 2016, 8 (3), 685-696.

Morelli, Massimo, “Political participation, populism, and the COVID-19 Crisis,” voxEU.org, 8 May, 2020.

Olivola, Christopher Y, Helen Susannah Moat, and Tobias Preis, “Using big data to map the relationship between time perspectives and economic outputs,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2019, 42.

Pargament, K.I., The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice, Guilford Press, 2001.

Pew (2020a) “Few Americans say their house of worship is open, but a quarter say their faith has grown amid pandemic,” Pew Research Center, Fact Tank, 2020, April 30.

Pew (2020b) “Most Americans Say Coronavirus Outbreak Has Impacted Their Lives,” Social and Demographic Trends, 2020, March 30.

Sibley, Chris G and Joseph Bulbulia, “Faith after an earthquake: A longitudinal study of religion and perceived health before and after the 2011 Christchurch New Zealand earth-quake,” PloS one, 2012, 7 (12), e49648.

Stephens-Davidowitz, Seth, “Googling for God,” Opinion, New York Times, 2015

Yeung, Timothy Yu-Cheong, “Measuring Christian Religiosity by Google Trends,” Review of Religious Research, 2019, 61 (3), 235-257.